Alice Calaprice is the editor of the hugely popular collection of Einstein quotations that has sold tens of thousands of copies worldwide and been translated into twenty-five languages. This is the story of how her knack for German and quest for full-time work in Princeton, New Jersey led her to a career she never imagined.

As a child I did not dream of someday becoming an author of books about Albert Einstein, nor did I contemplate the possibility even after graduating from UC Berkeley in the 1960s. Such an idea would not even have occurred to me. Along with my interest in science, languages, cultures, and history, it was eventually serendipity that took me there.

In the late 1970s, after my family had settled well into the routine of raising school-age children in Princeton, New Jersey, I assigned myself the task of finding full-time work. I had recently completed a course in the then relatively new field of computer technology, hoping it would help bolster a future career. One day in early 1978, a friend told me about a new venture being undertaken by Princeton University Press: the publication of the papers of Albert Einstein in a voluminous series that would span many years. An intriguing project, for sure, but I did not imagine myself being a part of it.

Soon after, however, the founding editor of the project, physicist John Stachel, and I met after he had started some preliminary work on the papers. It interested him that I was a native German speaker, had spent time around computers, and wasn’t averse to physics jargon and working with physicists, being married to one at the time. He had been looking for someone for a specialized task: helping him prepare three electronic indexes of the contents of the Einstein archive. He explained that the archive contained about 10,000 documents, consisting of Einstein’s writings, correspondence, and third-party materials. The indexes would give him an overview of the archive’s size and contents—information crucial to the planning stages of the enormous undertaking. Although the Collected Papers of Albert Einstein would be administered and published by the university press, the archive and his office were located at the nearby Institute for Advanced Study, in the same building where Einstein himself had worked during the last two decades of his life. Stachel asked if I was interested in helping to jump-start this initial phase of the project. The timing turned out to be perfect, and I agreed. I had no inkling that I was about to jump-start a lifelong career as well.

This assignment, which required perusing and often carefully reading each document in the archive’s files, gave me the chance to familiarize myself with the details of Einstein’s legacy and life, with which I was not particularly familiar. It was also an opportunity to revive my long-neglected German-language aptitude, which had waned over the years. Einstein wrote almost exclusively in his native language, even after he came to America from Germany in 1933; his correspondence and papers were generally translated by his secretary or assistants. I was surprised by some of the particulars about his life. He was not so saintly, after all, and besides transforming scientific thinking he had also done ordinary things like play the violin and love animals. My curiosity was piqued.

I quickly became an autodidact, reading supplementary articles and books so I could put the archival material into context. Names of Einstein’s family, friends, and colleagues became familiar, as did the terms for concepts in physics used by him and his cohorts. The prewar and wartime venues and events in Germany became clearer, alive, and more personal.

I quickly became an autodidact, reading supplementary articles and books so I could put the archival material into context. Names of Einstein’s family, friends, and colleagues became familiar, as did the terms for concepts in physics used by him and his cohorts. The prewar and wartime venues and events in Germany became clearer, alive, and more personal. Berlin, the city of my wartime birth, took on new meaning: I discovered that the Einstein family had lived in the same neighborhood as my family, but, unlike them, we did not have to flee persecution. We did flee the city during the Allied bombings of 1945, long after the Einsteins had already departed for America. After short stints in various villages, we coincidentally ended up in Bad Cannstatt in southwestern Germany, which I later learned was also the ancestral home of Einstein’s mother. And, finally, both of us had found our way to Princeton, if at different times, by different routes, and for different reasons. I loved coming to work. I had found a stimulating job that suited me well. Not only was the timing of my employment in the archive ideal for me personally, but the times were exciting, too. The centennial of Einstein’s birth took place at the Institute—among other worldwide venues—in 1979. Some of Einstein’s assistants and collaborators were still alive and gave firsthand accounts of their recollections in a symposium on the campus. I was able to attend these talks. Einstein’s Inner Circle There and at other times, I met many people who had been associated with Einstein either directly or were now members of boards that were planning the eventual publication of his papers.

Outstanding among these was Helen Dukas, Einstein’s longtime, modest, and intensely loyal secretary, who, after his death in 1955, had become the first archivist of his papers. Now in her early eighties, she still came to work almost daily. Her office was around the corner from mine on the third floor of Fuld Hall. She stopped by to chat every morning after exiting the elevator located across from my office, often inspecting the never-ending clutches of house finches nesting outside my window in spring and summer. She came to our house for dinner, and she invited my family to be her guests at the swimming pool in the Institute Woods. At Helen’s crowded memorial service after her death in 1982, I heard her old friend Otto Nathan, the executor of Einstein’s estate, tearfully proclaim, “When Helen died, Einstein died a second time.”

The Institute, a cosmopolitan place of world-renowned scholars, where foreign languages were heard more often than English, was a place where one could thrive professionally and personally. We completed the indexes by the 1980 deadline. Because the 10,000 estimated documents had more than quadrupled to 42,000, we had hired a part-time assistant to help accomplish the task. I spent long hours working off-site in the evenings, when mainframe computers at the university’s Computer Center and, later, in my husband’s cyclotron laboratory in the physics department, were more readily available for use. Herb Bailey, the well-regarded director of Princeton University Press who had long advocated for publication of the Collected Papers, was apparently pleased with my work. He now offered me a position in the editorial offices at the Press’s historic Scribner building on the university’s campus.

My first day of work was on April Fool’s Day 1980, but I was assured my employment was not a joke. John Stachel continued his sole editorship of the papers at the Institute, and later at Scribner with a small staff. I was in touch with the group almost daily, grounding my interest in what came to be known as the Einstein Papers Project. Fluent in Einstein Five years later, after I had become a senior editor at PUP, I had the opportunity to again read the documents and letters that were about to be published in volume 1 of the Collected Papers. In 1985, the first manuscript in the series was turned over to the Press’s editorial office, and I was asked to take charge. I helped to set an editorial style for the series, copyedited the volumes as they arrived in-house, and became administrator and “principal investigator” of the concomitant National Science Foundation-funded English-translation project.

Over a span of almost thirty years, I copyedited all fifteen of the volumes in the series—more recently as a freelancer—that have been published so far, including the translated volumes. Alas, so much reading, yet I never succeeded in understanding physics and relativity theory! Despite this shortfall, I became the liaison for nonscientific Einstein-related inquiries, book projects, film documentaries, and even the movie IQ in the early 1990s. I was a resource on matters dealing with Einstein, consistently learning something new in the process and having contact with an assortment of Einstein aficionados around the world. At the same time, I handled many other editing projects, mostly in the sciences. Surrounded by a group of wonderful, supportive, and good-humored colleagues and a continuously changing stream of engaging authors, I was having the time of my life. Those years set the stage for the twenty years ahead.

In 1995, I had an especially good year. First, it was the year I began mitigating my restlessness at home by taking annual trips to unlikely parts of the world, and I went to eastern Siberia with a small group of fellow nature lovers. Second, on my return, I received the news that I would receive the national Literary Market Place (LMP) Award for Individual Editorial Achievement in Scholarly Publishing, to be presented at the New York Public Library the following year. Third, Trevor Lipscombe, PUP’s acquisitions editor in physics at the time, discussed with me the prospect of publishing a book of quotations by Einstein. Like all those familiar with Einstein’s life, Trevor was aware that the physicist was multidimensional and fearless in expressing opinions on a variety of topics of interest to many: there was much more to him than relativity theory. Unbeknownst to Trevor, I had already collected many quotations while working on the indexes and copyediting the first few volumes of the Collected Papers—simply because they had struck a chord with me. When I showed him my blue box of index cards containing the quotations, he suggested I write the book myself rather than find someone else to do so. I was excited at the prospect of being on the other side of the author/editor relationship.

I believe these books were successful because they showed Einstein in all his guises, in his own uncensored words—a human being beyond the prevailing hagiographic and absent-minded-professor myths and falsely attributed quotations.

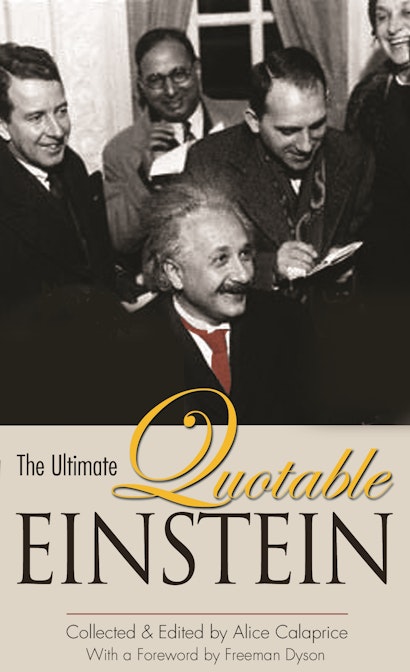

Soon after I returned from another adventure trip about a year later, this time into the Amazon Basin in northeastern Peru, the first edition of The Quotable Einstein was published. It contained four hundred quotations and their sources, arranged by topic, such as Einstein on religion, on his family, on Jews, on politics, on science and scientists, and so forth. The initial print run was modest, as there were doubts that the book would have wide appeal. The volume quickly sold out, however, and was reprinted six times. For a long time, it was at the top of PUP’s sales list, which I admired in disbelief and awe whenever one was posted on the bulletin board. Three more enlarged editions followed at approximately five-year intervals, and more than twenty-five foreign-language translations have been contracted, some in obscure languages I had never heard of. I believe these books were successful because they showed Einstein in all his guises, in his own uncensored words—a human being beyond the prevailing hagiographic and absent-minded-professor myths and falsely attributed quotations. The Ultimate Quotable Einstein, containing about 1,600 documented quotations and published in 2008, was my fourth and final contribution to this series of quotation books.

Because of the success of these volumes, I was now, to my surprise, perceived as an authority. I was asked to give talks for nonacademic audiences and participate in television shows and documentaries. I was invited to the German embassy to celebrate the special relativity centennial in 2005, and sat next to the German ambassador for lunch. I had book signings. I appeared on Ira Flatow’s “Science Friday” at the NPR studio in New York, along with Dennis Overbye of the New York Times. I have to confess that I found these new challenges difficult. I felt more comfortable doing research and writing, so I agreed to write three more books for other publishers who approached me. Now, well into retirement in California, I am back with PUP for my swan song in the Einstein genre. Having often felt the need for a concise Einstein reference guide while doing research, I had submitted to the publisher an informal proposal to write An Einstein Encyclopedia. My expertise on specialized topics relating to Einstein is limited, so two Einstein scholars with broad experience on the Einstein Papers Project, historian Robert Schulmann and physicist Dan Kennefick, fortunately agreed to join me in this project as co-authors. Our final proposal was accepted, the three of us had a productive long-distance collaboration, and, best of all, we managed to stay friends throughout the process. As our reward, we are now the proud authors of a reference book that we expect will be of use and interest to an eclectic readership.

Alice Calaprice is a renowned authority on Albert Einstein and the author of several popular books on Einstein, including The Ultimate Quotable Einstein (Princeton).