For a century we’ve abided each other,

Giving our brotherly due.

You abide that I breathe,

And, though you rage, I abide you.

But occasionally, in dark times, good spirits in full flood,

Your tender, pious little paws have colored my blood.

Our friendship is firmer. It grows stronger as we age.

I’m becoming almost like you,

I, too, am beginning to rage.

Heinrich Heine “An Edom” (1824)

Today, almost all the animals in the world do not and cannot determine their destinies. It was not always like this. Before the emergence of human beings thousands of years ago, animals were free to roam the planet as they wished. Meanwhile, humans gradually evolved and sought ways to survive under difficult conditions: they were compelled to prove their superiority to everyone and everything that inhabited the earth. To protect themselves and live more comfortable lives, they began using and killing animals at their will. Moreover, they ate the beasts, used them in various ways, and drove them to flee from their homes. In each century of the modern era, humans found new ways to maltreat animals. They constantly sought to prove their superiority as a species or race. So, eventually, humans caged animals and put them on display in homes as well as in zoos and circuses. They “milked” them of their pride and natural way of life. Animals became slaves.

To show how humans needed, loved and admired animals, they created races for dogs and horses. They set animals against one another and bet which one could kill the other. They taught them how to drag carriages and coaches. Humans love the animals they trained in their civilizing processes. Of course, animals had no choice but to obey or flee their superiors. Yet, by the nineteenth century, there was really nothing more animals could do to protect themselves, for the humans developed powerful weapons and invaded forests and jungles to demonstrate how smart and unique they were. The animals were no match for the humans and their weapons. They were game for humans. Easy game. It was as if the animals had to play the game with their legs tied because the humans had developed precise technological weapons. Even the weakest human in the world could kill an animal without being arrested.

Wikipedia explains that “hunting is the practice of seeking, pursuing and capturing or killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to harvest useful animal products… . . Recreationally hunted species are generally referred to as the ‘game,’ and are usually mammals and birds. A person participating in a hunt is a hunter or (less commonly) huntsman; a natural area used for hunting is called a game reserve, and an experienced hunter who helps organize a hunt and/or managing the game reserve is known as a gamekeeper.

Wikipedia forgets to name hunters for what they are—murderers.

Felix Salten (1865–1945) was a kind of recreational murderer, but he was also the prey of Nazi fascists. He was born with the name Siegmund Salzmann, and when his family moved to a working-class neighborhood in Vienna, he experienced anti-Semitic attacks both from students and teachers. When he met some of the most cultured Jews of the Young Vienna movement in the Café Griensteidl as well as some gentile aristocrats, he changed his name and desired to become like them. In fact, given his unusual talent as journalist, playwright, novelist, and hunter, Salten became one of the most popular writers in Vienna. Moreover, he was also known as a lover of animals.

In many ways Salten understood animals better than the veterinarians of his day. As a Jew, he also knew what it meant to be persecuted and killed. He knew how difficult it was to assimilate and play by the rules of society that he and his ancestors had not created. And even when some Jews could set the rules, they did not do much better than their persecutors. This is what some historians call the perverse continuity of history. What is also perverse is the manner in which Salten’s “historical” testimony has been sweetened by the Disney company and other cultural vultures to eliminate the lonely struggle he fought to be recognized as an Austrian aristocrat—that is, a killer with a heart.

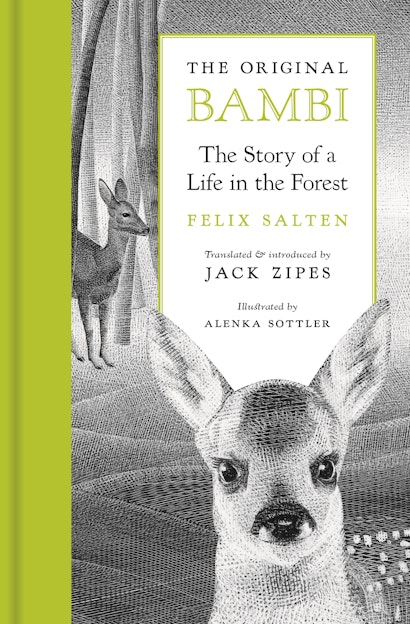

In 1921, Salten wrote the most poignant novel of his career, Bambi, The Story of a Life in the Forest. Though most publishers, academics, and educators, have categorized Bambi as a novel or film for children, they are completely wrong. Salten never wrote this book for children, and it is time that we recognize Bambi as a work that anticipated the devastation of European Jews and also draws parallels with the way that minorities are treated in various countries throughout the world. Salten believed that loneliness marked the lives of outsiders. His metaphorical novel speaks the truth not only about his life but also about all people designated as the prey in a game that elites still play for their own benefit.

Felix Salten (1869–1945) was an Austrian novelist, journalist, and critic. Jack Zipes has written, translated, and edited dozens of books, including The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm and The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (both Princeton). He is professor emeritus of German and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota. Alenka Sottler is an award-winning painter and illustrator who lives in Ljubljana, Slovenia.