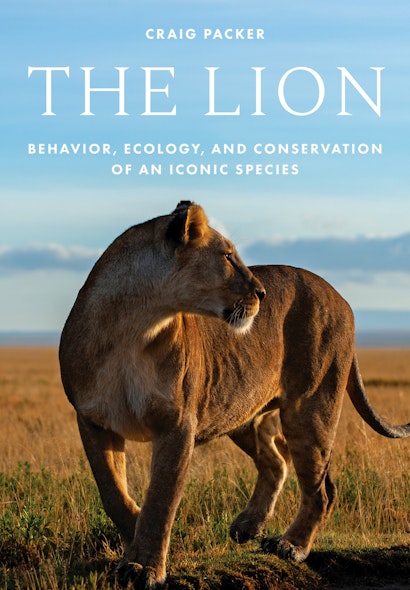

The temperature is climbing, and the great outdoors is teeming again with flowers, insects, birds, and other creatures of all shapes and sizes. To celebrate the coming of summer, we asked several of our naturalist writers and scholars to respond to the following question: How did you fall in love with natural history? This week, we hear from Dr. Craig Packer, a professor at the University of Minnesota and author of The Lion: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation of an Iconic Species.

Few animals hold the same grip on the human imagination as the African lion, and, in a world of shrinking wilderness, nowhere evokes such a breathtaking sense of nature as the sight of a million wildebeest migrating across the Serengeti with its wide-open spaces and tree-lined river crossings. For many, George Schaller was our first encounter with the ultimate predator and its iconic home with his landmark book, The Serengeti Lion. I hadn’t yet started high school when Schaller first arrived in the Serengeti in March 1966. In those days, I spent each school year with my parents in Fort Worth, Texas, but my summers were always on my grandmother’s farm a few miles from the town of Noodle, Texas. Her farm was only a few hundred acres of poor soil with modest harvests of wheat and sorghum that were just enough to get by from one year to the next. I helped with the chores, clearing brush, and occasionally driving the tractor, but I otherwise took every opportunity to go fishing or wander around outdoors until it got too hot in the afternoon. I had little idea what I wanted to do with my life, except I was determined to be a scientist—I was always curious about everything and reckoned that scientific research would be the closest I’d ever get to becoming a twentieth-century explorer. Oddly, though, the white-coated stereotypical scientist of the time invariably worked in a sterile laboratory with test tubes or caged rodents, and I had a profound aversion to being trapped indoors.

By the time Schaller’s book came out, I happened to be in Tanzania, working as an undergraduate field assistant for Jane Goodall at Gombe National Park and helping to set up a long-term study on olive baboons that paralleled Jane’s famous chimp project. I went out every day noting down all the individuals I saw, who was mating with whom, who had given birth to which baby. I also helped bridge the gap back to several earlier projects at Gombe, lining up their prior IDs with the current individuals. I can still remember the thrill of realizing that Asparagus had two older sisters, Apricot and Apple, thus making Azalea the grandmother of Algae. They not only bore a family resemblance, but their relationships were different with each other than with anyone else. I spent most mornings in the forest just up the hill from the shores of Lake Tanganyika, following a particular baboon for two hours at a stretch, collecting data on young males before and after they left the troops of their birth to start breeding in neighboring troops. The work required long hours outside, surrounded by nature, absorbed by the lives of another species—and my teenage fantasies of somehow doing science outdoors materialized almost too neatly in ways that could hardly have suited me better.

I read Schaller’s lion book during my first year in graduate school—and though I was fascinated by his descriptions of the lions and their world, it was the simultaneous publication of The Spotted Hyena by Hans Kruuk that truly captured my imagination. Kruuk had been a student of Niko Tinbergen, the Nobel Prize–winning ethologist who founded the field of behavioral ecology—which seeks to understand the evolutionary underpinnings of animal behavior—and Kruuk had collected quantitative data to test specific hypotheses about the survival value of specific aspects of hyena behavior. Hyenas may not be much to look at compared to lions, but their lives are every bit as interesting—even when reduced to a series of precise measurements of grouping patterns and hunting tactics. Thus inspired, I addressed specific hypotheses about the risks and benefits to a male baboon from leaving his mother’s troop and entering a neighboring troop. But I had also learned an important lesson from Jane: sometimes the most valuable insights come from just watching the animals without any preconceived notions; don’t forget to allow yourself to be surprised by things that you’d never contemplated before.

Craig Packer is Distinguished McKnight University Professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior at the University of Minnesota. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science and is the award-winning author of Into Africa and Lions in the Balance: Man-Eaters, Manes, and Men with Guns.