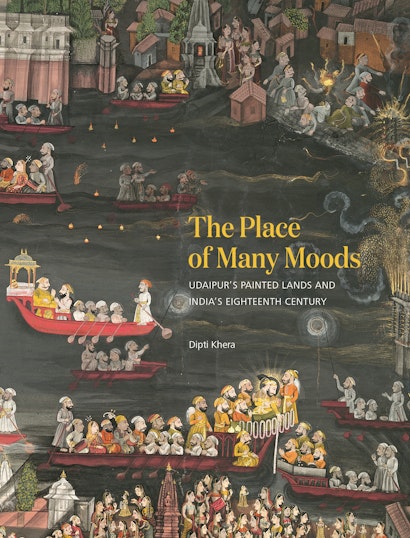

In the long eighteenth century, artists from Udaipur, a city of lakes in northwestern India, specialized in depicting the vivid sensory ambience of its historic palaces, reservoirs, temples, bazaars, and durbars. As Mughal imperial authority weakened by the late 1600s and the British colonial economy became paramount by the 1830s, new patrons and mobile professionals reshaped urban cultures and artistic genres across early modern India. The Place of Many Moods explores how Udaipur’s artworks—monumental court paintings, royal portraits, Jain letter scrolls, devotional manuscripts, cartographic artifacts, and architectural drawings—represent the period’s major aesthetic, intellectual, and political shifts.

In recounting memorable times—catastrophic or celebratory—why do we often start by describing the feel of a place where relevant episodes unraveled? We deploy stories and look for pictures. We turn to descriptions and tropes adopted by others, embedding our experiences and imaginings into their representations, even mixing times, actors, and vignettes. We exaggerate; we censor. We strive to capture the precise mood of a place and time conjured up in mental images, even if that means idealizing evocations, adapting details, and using imprecise associations. Nonetheless, each representation of moods creates effects that are unmistakably historically contingent.

From the vantage point of the lake city of Udaipur, since around 1559 capital of the erstwhile regional court of Mewar and part of the contemporary state of Rajasthan, The Place of Many Moods tells the story of such deep investments in picturing the moods of a place in the long eighteenth century. Concurrently, as Mughal imperial authority weakened by the late 1600s and the British colonial economy became paramount by the 1830s, new patrons and mobile professionals across early modern India reshaped urban cultures and artistic genres. Udaipur’s painters make familiar places visible in unfamiliar ways, thereby revealing pasts, politics, and passions not always recorded in words. These memorialized moods confront the ways colonial histories have recounted Oriental decadence—and deployed eighteenth-century British picturesque landscapes as descriptions of physical lands, architectures, and peoples in civilizational decline—shaping how a culture, art, and time are perceived.

Picturing lands has always been tied to politics, poetics, and embodied practices on the ground. British narratives of ruination and colonial restoration motivated my pursuit of objects, texts, and travels that collectively constitute an intersecting, yet discontinuous, archive from which I write the history of painted lands as well as of India’s eighteenth century. Since the third century, the poets and intellectuals who shaped premodern aesthetics recognized the art of generating bhāva—a word encompassing moods, emotions, and feelings. Udaipur’s early modern painters expanded the conceptualization of bhāva on visual and material terms. They give visual form to their enchantment with the valley’s sustaining hills, lakes, and flowing streams, rendering the moods of the material world around them—the vivid sensory ambience of its lime-washed white palaces, reservoirs, temples, bazaars, and durbars. Their grand-scale paintings, much larger than smaller folios of royal portraits and devotional manuscripts capable of being held in a single hand, reveal powerfully immersive and politically contingent conceptions of a place’s bhāva and an overlooked art that passionately praised places.

Let us see and sense the mood of a monumental monsoon. A painting dated to around 1700, measuring nearly six feet wide and four feet high, Maharana Amar Singh II in Udaipur during a Monsoon Downpour, was likely among the earliest large-scale paintings created by Udaipur’s artists. A topographic vision of the city’s hills and lakes—beyond the palace precincts—engulfed in slate-grey clouds and stormy rains covers half of the primed cotton ground. Against this backdrop, the ruler Amar Singh II is seated in a public hall, alongside his nobles, watching the staged spectacle of an elephant running amok, depicted nine times to denote his swift motions. The painting does not allow its audience a simple, singular focus. The painter composed the eastern façade of the palace a from a fish-eye point of view; he presents the outer courtyard from birds-eye perspective, and he stretches the width of the courtly hall such that the viewer’s eye is drawn to the royal party. One participates in unraveling a setting bursting with painterly details. The layer of white painted strokes of pouring rain that literally flow into the silvery gray lakes and streams. We feel the movement of waves created by feather-like semicircular paint strokes. The unfolding of a temporal spectacle is heightened by the rain pouring from dark, heavy clouds painted in thick gouache. A sense of immediacy sweeps over the valley, the painting, and the viewers of this loud cloud burst.

For both politics and culture, the grounds for loyalties, personal friendships, and representation had shifted by the late-seventeenth century. Mughal imperial authority was largely restricted to its capital in Delhi. Regional courts flourishing in the cities of Jaipur and Lucknow reimagined their place in distinctly local and urban ways—through painting, poetry, cartography, and city building. Udaipur’s painters and patrons, led by Amar Singh II realized the potential their city’s unique locale, microclimate, and natural resources offered to hold new political communities together. The mid-sixteenth century founders of the city had carefully considered the dual perspective of finding a secure terrain and of creating reservoirs for holding large quantities of water. Early literary accounts highlight Udaipur’s dams, wells, waterfronts, and many of its manmade lakes. Maharana Amar Singh II in Udaipur during a Monsoon Downpour visually presents the serpentine channels that feed water into the central Lake Pichola around which life flourishes.

One way to parse how Udaipur became the place of rain and lakes in the courtly imaginary is to recognize the central relationship painters established between the enduring and the ephemeral. Amar Singh II’s patronage for these large artworks was decidedly tied to his best-known building project, the Baadi Mahal (literally “the garden palace”). Built such that a hillock sixty feet high was enclosed within its retaining walls, the garden-palace became a part of the contiguous palatial facade overlooking the Manek Chowk—the large courtyard in front of the facade of his palace.

This rectangular courtyard, bounded by the imposing architecture of the Men’s Palace was a significant space even before the early 1700s. The early eighteenth-century painters, though, seem mesmerized by the palace’s monumentality—enlarging their canvases as if to accommodate both its spell and its size. Its towering pavilions, punctuated with domes, prominent octagonal domed turrets, projecting balconies, pierced screens, and windows with colored glass, form the highest story on the northern end of the palace, altering the skyline for the palace’s and city’s inhabitants alike. The panoramic plentitude of the monsoon downpour was made possible by the newly built Baadi Mahal. Its three wings offered consummate views of mountains, lakes, and environs beyond the palaces. The painter oriented the northern walls of the structure in the direction of the view one would see from being high up in the space of the garden palace—the town toward the north (the painting’s right side) encircling the palace complex from the northwest to the west as the clouds descend on the valley.

The pink-buff color the painters deployed to denote the retaining walls of the garden-palace further demarcates the vantage point from which the monsoon moods of Udaipur could be best observed and sensed. Its painters’ collated views drawn and observed from multiple vantage points—centered on ephemeral subjects, from the elephant spectacle to rains, streams, clouds—to collectively suggest a radically new viewing experience from higher altitudes.

But any attempt to privilege empirical observation and architectural knowledge as a key pictorial concern is stymied by the myriad associations painters and paintings established among overlapping genres and material realms. Poets and singers across early modern India described the transformation of human emotions with the onset of the monsoons. The celebrated rainy season in the poetry of the rāgamālā (garland of musical notes) and bārah-māsa (twelve-month sequence) expressed a heroine’s longing for her lover. Painters captured affect-saturated verses about the feeling of love in separation and union invoked by the sensate atmospheres of the seasons of monsoon and spring in manifold painterly and iconographic ways. The imagery of monsoons included besotted lovers, lightning streaks, thundering clouds, lotus-filled lakes, crying peacocks, roaring lions, and rutting elephants. Even when verses were not inscribed on paintings, the citation of familiar images and tropes, across innumerable monsoon paintings specific to Udaipur, persuades us that historical connoisseurs would have related these rain-drenched painted visions of their own lake-city of Udaipur to aspects of the idealized literary descriptions that circulated within courtly contexts and beyond.

In contrast, chronicles like the Jain monk-poet Jaichand’s Saīkī (A history of a hundred years) raises questions about how painters connected with their ever-changing environment, and how a painting presenting the feel of a monsoon downpour at Udaipur, not circumscribed by one text or genre, could have been received at the court. From Jaichand’s more practical perspective, the paintings of rains take on additional urgency. Almost each six-line verse in Jaichand’s history begins with an abbreviated reference to the years it chronicles, spanning from 1658 to 1714. These sets of verses recount the nature of political conflicts and alliances, followed by a report on yearly rains and associated conditions of agricultural production, economy of the grains markets, and migration patterns of people. Ultimately by alternating between the political story and ecological story, Jaichand aims to create a picture of dukāl, bad times, and sukāl, good times. Prosperity and morality are linked to ecology and politics. Both are steeped in crisis. Both change year upon year. Storms, droughts, floods, migrations, price fluctuations, are the measure of time as much as, if not more than, the reigns of kings.

So, what does Jaichand have to say about political time and ecological time in 1699, at the dawn of Udaipur’s Amar Singh II reign? Sukāl, good times! A few years later, in 1704, he celebrates prodigious rains that arrived across the seasons of summer and monsoon, though we learn of yet another season of drought in 1705.

Jaichand’s telling of the history shifts our interpretation of the monumental monsoon mood, not simply because the painting maybe a historical document of a flourishing monsoon. We learn instead that the stakes of idealizing monsoon moods were high and associating their seasonal pleasures with a protracted kingly temporality rather than annual chronological time could have been an expedient move on behalf of painters, patrons, and scribes. Far from being decadent or dispensable luxuries, the paintings of rains and lakes memorialized the bhāva of a prosperous year, so that it could be returned to when fortunes changed.

Amplification of the scale of paintings constitutes a meaningful material choice for the ways it made the painted subject powerful, but also for the radically different potential for perception and of enchantment by the object. It is tempting to imagine that courtly connoisseurs—nobles and landholders in Amar Singh II’s court—might have savored the cooling water-drenched vision in the summer heat, possibly even ascribed efficacious power to the object, that it could bring their desires for a good monsoon to fruition, its affective power enhanced by its expanded scale and composition. In featuring thriving moods of urban places a potentiality was actualized in such painted artifacts. These representations cultivated a sense of bonding to places, keeping the image of the momentousness associated with the arrival of rains and the forever-plentiful lakes of Udaipur close to the heart and mind. The localizing of distinct kinds of celebratory moods was ultimately tied to pushing boundaries on real lands.

The study of landscape in art history cannot escape its ties to—colonialism, race, empire, ecology, identity, nationalism, global travels, and extraction of resources. The emergence of landscape painting in eighteenth-century Britain (and beyond) as a distinct kind of artwork underscores the new emphasis on affect, aesthetic theory’s shift from production to reception, and the role of taste in defining beauty. The project of figuring the bhāva of a place tells us that conceptualizations that may come from off-center geographies and off-center objects have much to offer. The messy projects of art history do not only entail generating “knowledge” for a discipline classified into regions along a teleological model; they moreover demand the willingness to learn by not only comparing and connecting but also conceptually entering into new terminologies and archives on equal theoretical and analytical footing. That is, we evaluate the primacy of iterating and sensing moods, imagining the work of moods in their own times but also consider moods of a place as a productive idea to think with.

Next month in this space, Khera will share the story of a 72-feet long painted invitation letter, which was created in Udaipur’s bazaars in 1830. She has experimented with recreating the experience of digitally scrolling down the painted streets on this paper scroll on a new website, which supplements the interpretation and reproduction of the letter-scroll in 12 parts in The Place of Many Moods. It will make this extraordinary artifact, housed in the collection of the Abhay Jain Granthalaya, Bikaner, available to wider publics for further research.

Dipti Khera is associate professor in the Department of Art History and the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Twitter @KheraDipti

Notes

To see the details of the painting Maharana Amar Singh II in Udaipur during a Monsoon Downpour, c. 1705, Udaipur, see here. For details of painting Maharana Sangram Singh II at the Gangaur Boat Procession, c. 1715–20, Udaipur, and the architecture and collections of the City Palace Museum, Udaipur, see here.