I first arrived in Turkey as a young woman in 1975 to study at Ankara’s Hacettepe University, unaware that Turkey was experiencing a low-level civil war. My first clue was right outside the airplane in which I landed, where a strange, ungainly vehicle with a mounted gun was parked on the tarmac right below the exit stairs. I soon learned to recognize this as an armored personnel carrier or APC. They were stationed in every main square, menacing the traffic, ready to leap into action. I learned how fast they move when one day, carrying a sack of laundry through a crowd, I came face to face with two of them blocking the road. They looked enormous. They began to move towards us, then sped up and charged the crowd. Someone pulled me out of the way just in time and threw me into a protective doorway. Clutching my laundry, I joined some others running down a side street. The APCs leapt onto the sidewalk with great agility, like enormous cockroaches, and chased us.

Once at the university, I experienced much more first-hand. Various flavors of the left fought pitched battles against each other and against right-wing youth groups. The university, like the city streets, was full of soldiers, there to keep the peace between feuding groups of students. Explosions and gunfire were so common that they were barely noticed. The country was tearing itself apart in a bloody feud that infected everyone, from grade school to university, village to city, whether they wanted to participate or not. There was no middle ground. There were parallel police forces and governments; even the army was split. Between 1976 and 1980, 5,000 civilians were killed in street violence. During all of this, people went about their lives, falling in love, working, studying, meeting friends, starting families, and planning for the future.

A coup d’état in 1980 replaced street violence with the more efficient violence of the state that brutally repressed activists, particularly on the left. Three years later, the military allowed new elections and a civilian government came into power that pushed economic reforms and opened Turkey’s closed economy to the global market. This began a colorful, globalized era in which Turks strove to become upwardly mobile consumers. The terror of the 1970s was largely forgotten or, better said, repressed.

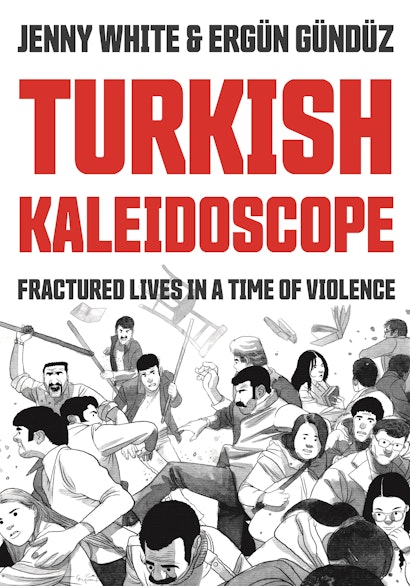

Today, I’m a social anthropologist studying contemporary Turkish society and politics. My new book, Turkish Kaleidoscope, explores the 1970s from the perspective of everyday lives. It’s based on my own experience as well as dozens of oral history interviews that I carried out in Turkey with a wide variety of people, both activists and bystanders, men and women, left and right, rich and poor, and from different social, religious and ethnic backgrounds. The interviews provided a rich and textured picture of the period, a ‘history from below’. People’s memories were vivid and they seemed to relive their experiences as they spoke. Their accounts included political violence, but also moving and thought-provoking coming-of-age stories.

These have been merged and fictionalized to tell the stories of four college students, two on the left and two on the right. We see the characters in their youth and follow them to Ankara to study. We witness them initiated into violent group activity and how that group becomes their life, every aspect of which is controlled by the group leader. Sexuality and love are heavily policed. The book moves through the decade until the 1980 coup and ends with several scenes set in present day Istanbul as two of the characters meet again by chance decades later.

Why a graphic novel? Academic analysis flattened these stories into discussions of abstract issues, like factionalism. A graphic novel explains the same things in a more subtle way, retaining the nuances and contradictions of history as it is lived. I was privileged to work with the talented Turkish artist Ergün Gündüz. When I first came to him with a densely written 80-page storyboard, he patiently pointed out that he couldn’t draw what was in people’s heads. Many drafts later, I came up with something that could be drawn. It was truly a challenge to encapsulate my entire analysis in graphic action and a few speech bubbles.

Turkish Kaleidoscope exposes the multiple roots of political violence. The book doesn’t give an ideological or event-driven analysis, but asks more universal questions about what causes people to sacrifice their lives, health and relationships for a cause or for an autocratic leader, to engage in violent acts, and, in the end, to break away from that cause or leader. What effect, if any, do their actions have on society, on their own lives and those of their children? From the vantage point of people on the ground, these questions take on a universal quality that speaks to contexts beyond Turkey and beyond the 1970s.

Jenny White is a social anthropologist and professor at the Stockholm University Institute for Turkish Studies. Her many books include Muslim Nationalism and the New Turks (Princeton) and the novel The Winter Thief. She lives in Stockholm. Twitter @WhiteJennyB

Also of Interest

Watch the Turkish Kaleidoscope book trailer and listen along to the Turkish Kaleidoscope Musical Playlist.